Vladimir Nabokov, Louise Glück

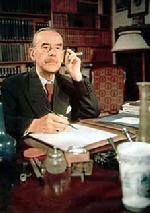

Der russische Schriftsteller Vladimir Nabokov wurde am 22. April 1899 als ältestes von fünf Kindern in St. Petersburg geboren. Nabokov studierte in Cambridge russische und französische Literatur. Die erste und wohl produktivste Phase seines künstlerischen Schaffens begann in Berlin, wo Nabokov von 1922 bis 1937 lebte. Er veröffentlicht unter dem Pseudonym "Vladimir Sirin" Gedichte, Dramen und Erzählungen. Auch erste Romane schrieb er dort, zum Beispiel "Maschenka" (1926) oder "Lushins Verteidigung" (1929/30). Seinen Lebensunterhalt allerdings konnte er mit der Literatur noch nicht bestreiten, er schlug sich mit Tennis-, Box- und Russischunterricht durch. Nach 15 Jahren verließ Nabokov mit seiner Familie das nationalsozialistische Deutschland und emigrierte nach Frankreich. Drei Jahre lebte und arbeitete er in Paris und Südfrankreich und vollendete seinen Roman "Die Gabe" (1937/38), der das Schicksal eines russischen Emigranten beschreibt.Im Jahr 1940 ging er in die USA, wo er von 1948 bis 1956 als Professor für russische Literatur an der Cornell Universität in Ithaka (New York) arbeitete. 1945 wurde Nabokov US-Staatsbürger. In Amerika begann auch seine zweite Schaffensphase. Er verzichtete fortan auf sein Pseudonym und veröffentlichte seinen ersten englischsprachigen Roman "The real life of Sebastian Knight" (1941). Weitere Romane folgten. Als eine der facettenreichsten Dichterpersönlichkeiten der Moderne veröffentlichte er 1955 "Lolita", jener Roman, über die pikante Affäre des 50-jährigen Humbert mit seiner 12-jährigen Stieftochter Lolita. Skandalumwittert, umstritten und oftmals missverstanden, machte ihn das Buch mit einem Schlag weltweit berühmt. Im Jahr 1961 verließ Nabokov mit seiner Frau die USA und kehrte nach Europa zurück. Sie ließen sich im schweizerischen Montreux nieder. Unter dem Titel "Sprich, Erinnerung, sprich" (1967) veröffentlichte Nabokov seine Autobiografie.

Aus: Speak Memory

“The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness. Although the two are identical twins, man, as a rule, views the prenatal abyss with more calm than the one he is heading for (at some forty-five hundred heartbeats an hour). I know, however, of a young chronophobiac who experienced something like panic when looking for the first time at homemade movies that had been taken a few weeks before his birth. He saw a world that was practically unchanged—the same house, the same people—and then realized that he did not exist there at all and that nobody mourned his absence. He caught a glimpse of his mother waving from an upstairs, and that unfamiliar gesture disturbed him, as if it were some mysterious farewell. But what particularly frightened him was the sight of a brand-new baby carriage standing there on the porch, with the smug, encroaching air of a coffin; even that was empty, as if, in the reverse course of events, his very bones had disintegrated.

Such fancies are not foreign to young lives. Or, to put it otherwise, first and last things often tend to have an adolscent note—unless, possible, they are directed by some venerable and rigid religion. Nature expects a full-grown man to accept the two black voids, fore and aft, as solidly as he accepts the extraordinary visions in between. Imagination, the supreme delight of the immortal and the immature, should be limited. In order to enjoy life, we should not enjoy it too much.

I rebel against this state of affairs. I feel the urge to take my rebellion outside and picket nature. Over and over again, my mind has made colossal efforts to distinguish the faintest of personal glimmers in the impersonal darkness on both sides of my life. That this darkness is caused merely by the walls of time separating me and my bruised fists from the free world of timelessness is a belief I gladly share with the most gaudily painted savage. I have journeyed back in thought—with thought hopelessly tapering off as I went—to remote regions where I groped for some secret outlet only to discover that the prison of time is spherical and without exists.”

Vladimir Nabokov (22. April 1899 - 2. Juli 1977)

Statue in Montreux

Die Amerikanische Lyrikerin und Schriftstellerin Louise Glück wurde am 22. April 1943 in New York geboren und hat an verschiedenen Universitäten gelehrt. Seit 1968 hat sie zehn Gedichtbände veröffentlicht, für die sie zahlreiche Preise erhielt, u.a. den Pulitzerpreis für "Wilde Iris", den Bollingen Prize und den National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry. 2003-2004 war Louise Glück Poet Laureate der Vereinigten Staaten. Sie lebt in Cambridge, Massachusetts. 2007 erschien bei Luchterhand ihr Gedichtband "Averno", mit dem sie 2006 auf die Shortlist des National Book Award for Poetry kam.

A Fantasy

I'll tell you something: every day

people are dying. And that's just the beginning.

Every day, in funeral homes, new widows are born,

new orphans. They sit with their hands folded,

trying to decide about this new life.

Then they're in the cemetery, some of them

for the first time. They're frightened of crying,

sometimes of not crying. Someone leans over,

tells them what to do next, which might mean

saying a few words, sometimes

throwing dirt in the open grave.

And after that, everyone goes back to the house,

which is suddenly full of visitors.

The widow sits on the couch, very stately,

so people line up to approach her,

sometimes take her hand, sometimes embrace her.

She finds something to say to everbody,

thanks them, thanks them for coming.

In her heart, she wants them to go away.

She wants to be back in the cemetery,

back in the sickroom, the hospital. She knows

it isn't possible. But it's her only hope,

the wish to move backward. And just a little,

not so far as the marriage, the first kiss.

Louise Glück (New York, 22. April 1943)

Aus: Speak Memory

“The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness. Although the two are identical twins, man, as a rule, views the prenatal abyss with more calm than the one he is heading for (at some forty-five hundred heartbeats an hour). I know, however, of a young chronophobiac who experienced something like panic when looking for the first time at homemade movies that had been taken a few weeks before his birth. He saw a world that was practically unchanged—the same house, the same people—and then realized that he did not exist there at all and that nobody mourned his absence. He caught a glimpse of his mother waving from an upstairs, and that unfamiliar gesture disturbed him, as if it were some mysterious farewell. But what particularly frightened him was the sight of a brand-new baby carriage standing there on the porch, with the smug, encroaching air of a coffin; even that was empty, as if, in the reverse course of events, his very bones had disintegrated.

Such fancies are not foreign to young lives. Or, to put it otherwise, first and last things often tend to have an adolscent note—unless, possible, they are directed by some venerable and rigid religion. Nature expects a full-grown man to accept the two black voids, fore and aft, as solidly as he accepts the extraordinary visions in between. Imagination, the supreme delight of the immortal and the immature, should be limited. In order to enjoy life, we should not enjoy it too much.

I rebel against this state of affairs. I feel the urge to take my rebellion outside and picket nature. Over and over again, my mind has made colossal efforts to distinguish the faintest of personal glimmers in the impersonal darkness on both sides of my life. That this darkness is caused merely by the walls of time separating me and my bruised fists from the free world of timelessness is a belief I gladly share with the most gaudily painted savage. I have journeyed back in thought—with thought hopelessly tapering off as I went—to remote regions where I groped for some secret outlet only to discover that the prison of time is spherical and without exists.”

Vladimir Nabokov (22. April 1899 - 2. Juli 1977)

Statue in Montreux

Die Amerikanische Lyrikerin und Schriftstellerin Louise Glück wurde am 22. April 1943 in New York geboren und hat an verschiedenen Universitäten gelehrt. Seit 1968 hat sie zehn Gedichtbände veröffentlicht, für die sie zahlreiche Preise erhielt, u.a. den Pulitzerpreis für "Wilde Iris", den Bollingen Prize und den National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry. 2003-2004 war Louise Glück Poet Laureate der Vereinigten Staaten. Sie lebt in Cambridge, Massachusetts. 2007 erschien bei Luchterhand ihr Gedichtband "Averno", mit dem sie 2006 auf die Shortlist des National Book Award for Poetry kam.

A Fantasy

I'll tell you something: every day

people are dying. And that's just the beginning.

Every day, in funeral homes, new widows are born,

new orphans. They sit with their hands folded,

trying to decide about this new life.

Then they're in the cemetery, some of them

for the first time. They're frightened of crying,

sometimes of not crying. Someone leans over,

tells them what to do next, which might mean

saying a few words, sometimes

throwing dirt in the open grave.

And after that, everyone goes back to the house,

which is suddenly full of visitors.

The widow sits on the couch, very stately,

so people line up to approach her,

sometimes take her hand, sometimes embrace her.

She finds something to say to everbody,

thanks them, thanks them for coming.

In her heart, she wants them to go away.

She wants to be back in the cemetery,

back in the sickroom, the hospital. She knows

it isn't possible. But it's her only hope,

the wish to move backward. And just a little,

not so far as the marriage, the first kiss.

Louise Glück (New York, 22. April 1943)

froumen - 22. Apr, 18:35