Konstantínos P. Kaváfis

Der griechische Lyriker Konstantínos P. Kaváfis wurde am 29. April 1863 als neuntes und letztes Kind von Charíklia Fotiádi und Pétros J. Kaváfis in eine griechische Kaufmannsfamilie hineingeboren, die in Alexandria mit dem Handel ägyptischer Baumwolle zu Reichtum gekommen war. Mit dem Tod des Vaters im Jahr 1870 übernimmt der älteste Bruder Geórgios die Filiale des Unternehmens in Liverpool. 1872 übersiedelt auch die Mutter mit den übrigen Kindern nach England, wo die Familie die Jahre bis 1877 wechselnd in London und Liverpool verbringt. Dort scheint Kaváfis eine englische Schule besucht zu haben. Gesichert ist der prägende Einfluss der englischen Jahre: Zeitlebens pflegte Kaváfis ein als manieriert geltendes Griechisch mit englischem Akzent, und seine ersten Gedichte schrieb er in englischer Sprache. Nach dem Konkurs (1876) des Unternehmens Cavafis & Co. kehrt die Familie 1877 nach Alexandria zurück. Kaváfis nimmt eine kaufmännische Ausbildung an einer griechischen Höheren Handelsschule auf. Politische Unruhen im Zuge der Nationalbewegung gegen das britische Kolonialregiment führen 1882 zu Angriffen auf die ausländische Bevölkerung Alexandrias, die Mutter flieht mit den jüngsten Kindern nach Konstantinopel. Hier beendet er seine kaufmännische Ausbildung und studiert, wie schon in Alexandria, die Schriften griechischer Autoren der Antike und der byzantinischen Zeit. Es wird angenommen, dass Kaváfis sich in den Jahren bis zur Rückkehr nach Alexandria (1885) seiner Homosexualität bewusst geworden ist, die Teile des späteren lyrischen Werks prägt. In Alexandria nimmt Kaváfis nach kurzen Phasen als Zeitungskorrespondent und als Makler an der Baumwollbörse 1889 eine zunächst unbesoldete Stellung als Sekretär im Amt für Wasserwirtschaft des Ministeriums für Öffentliche Bauten an. Erst nach 33 Jahren als Vertragsangestellter gab Kaváfis 1922, in der Position eines stellvertretenden Abteilungsleiters, die ungeliebte Brotarbeit auf. Unterbrochen von zwei Reisen nach Paris und London und von nur drei kurzen Aufenthalten in Athen verbringt Kaváfis auch die Jahre bis zu seinem Tode in der ägyptischen Diaspora, in einer Stadt griechischen Ursprungs. Sein Selbstverständnis hat er mit diesen Worten charakterisiert: „Ich bin kein Hellene, ich bin kein Grieche. Ich bin hellenisch.“ Nach erfolgloser Behandlung des 1932 in Athen diagnostizierten Rachenkrebses stirbt Kaváfis an seinem Geburtstag im Jahre 1933 in Alexandria.

Longings

Like the beautiful bodies of those who died before they had aged,

sadly shut away in a sumptuous mausoleum,

roses by the head, jasmine at the feet—

so appear the longings that have passed

without being satisfied, not one of them granted

a night of sensual pleasure, or one of its radiant mornings.

Übersetzt von Edmund Keeley / Philip Sherrard

The Afternoon Sun

This room, how well I know it. Now

they’re renting it, it and the one next door,

as offices. The whole house has been taken

over by agents, businessmen, concerns.

Ah but this one room, how familiar.

Here by the door was the couch. In front of that,

a Turkish carpet on the floor.

The shelf then, with two yellow vases. On the right―

no, opposite―a wardrobe with a mirror.

At the center the table where he wrote,

and the three big wicker chairs.

There by the window stood the bed

where we made love so many times.

Poor things, they must be somewhere to this day.

There by the window stood the bed: across it

the afternoon sun used to reach halfway.

...We’d said goodbye one afternoon at four,

for a week only. But alas,

that week was to go on forevermore.

Days of 1908

That year he found himself without a job.

Accordingly he lived by playing cards

and backgammon, and the occasional loan.

A position had been offered in a small

stationer’s, at three pounds a month. But he

turned it down unhesitatingly.

It wouldn’t do. That was no wage at all

for a sufficiently literate young man of twenty-five.

Two or three shillings a day, won hit or miss―

what could cards and backgammon earn the boy

at his kind of working class café,

however quick his play, however slow his picked

opponents? Worst of all, though, were the loans―

rarely a whole crown, usually half;

sometimes he had to settle for a shilling.

But sometimes for a week or more, set free

from the ghastliness of staying up all night,

he’d cool off with a swim, by morning light.

His clothes by then were in a dreadful state.

He had the one same suit to wear, the one

of much discolored cinnamon.

Ah days of summer, days of nineteen-eight,

excluded from your vision, tastefully,

was that cinnamon-discolored suit.

Your vision preserved him in the very act of

casting it off, throwing it all behind him,

the unfit clothes, the mended underclothing.

Naked he stood, impeccably fair, a marvel―

his hair uncombed, uplifted, his limbs tanned lightly

from those mornings naked at the baths, and at the seaside.

Übersetzt von James Merrill

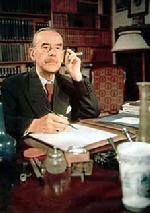

Konstantínos Petros Kaváfis (29 april 1863 – 29 april 1923)

Porträt von Thalia-Flora Karavia

Longings

Like the beautiful bodies of those who died before they had aged,

sadly shut away in a sumptuous mausoleum,

roses by the head, jasmine at the feet—

so appear the longings that have passed

without being satisfied, not one of them granted

a night of sensual pleasure, or one of its radiant mornings.

Übersetzt von Edmund Keeley / Philip Sherrard

The Afternoon Sun

This room, how well I know it. Now

they’re renting it, it and the one next door,

as offices. The whole house has been taken

over by agents, businessmen, concerns.

Ah but this one room, how familiar.

Here by the door was the couch. In front of that,

a Turkish carpet on the floor.

The shelf then, with two yellow vases. On the right―

no, opposite―a wardrobe with a mirror.

At the center the table where he wrote,

and the three big wicker chairs.

There by the window stood the bed

where we made love so many times.

Poor things, they must be somewhere to this day.

There by the window stood the bed: across it

the afternoon sun used to reach halfway.

...We’d said goodbye one afternoon at four,

for a week only. But alas,

that week was to go on forevermore.

Days of 1908

That year he found himself without a job.

Accordingly he lived by playing cards

and backgammon, and the occasional loan.

A position had been offered in a small

stationer’s, at three pounds a month. But he

turned it down unhesitatingly.

It wouldn’t do. That was no wage at all

for a sufficiently literate young man of twenty-five.

Two or three shillings a day, won hit or miss―

what could cards and backgammon earn the boy

at his kind of working class café,

however quick his play, however slow his picked

opponents? Worst of all, though, were the loans―

rarely a whole crown, usually half;

sometimes he had to settle for a shilling.

But sometimes for a week or more, set free

from the ghastliness of staying up all night,

he’d cool off with a swim, by morning light.

His clothes by then were in a dreadful state.

He had the one same suit to wear, the one

of much discolored cinnamon.

Ah days of summer, days of nineteen-eight,

excluded from your vision, tastefully,

was that cinnamon-discolored suit.

Your vision preserved him in the very act of

casting it off, throwing it all behind him,

the unfit clothes, the mended underclothing.

Naked he stood, impeccably fair, a marvel―

his hair uncombed, uplifted, his limbs tanned lightly

from those mornings naked at the baths, and at the seaside.

Übersetzt von James Merrill

Konstantínos Petros Kaváfis (29 april 1863 – 29 april 1923)

Porträt von Thalia-Flora Karavia

froumen - 29. Apr, 18:25